Theodore Roosevelt

They don’t get better than this—three volumes of Theodore Roosevelt, one of the most fascinating biographical subjects imaginable and a true inspiration.

The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt by Edmund Morris

Theodore Rex by Edmund Morris

Colonel Roosevelt by Edmund Morris

Tier One

When people ask me who my favorite president is, they are met with a long and rambling response wherein I name three or four presidents and refuse to pick one. It’s like picking your favorite child (or so I hear). Abraham Lincoln is our greatest president. Robert Caro’s series on Lyndon Johnson are the finest books written on a president. Ulysses S. Grant is the owner of my favorite single-volume biography. But Theodore Roosevelt is the most fascinating man to hold the office and, perhaps, the most fascinating of all Americans.

His life doesn’t seem possible. Sometimes, I’ll read an older history book set in Roman or Greek times, and I’ll wonder how anyone could’ve believed the tales being told about some near mythic person. It’s like people who believe that The Iliad or The Odyssey is history instead of poetry.

And then you read about Theodore Roosevelt and realize that in a thousand years, if anyone is around to read books and Morris’ monumental trilogy still exists, they’ll say the same things about Teddy.

A boy who couldn’t get out of bed and was beset with physical ailments that made it impossible for him to go outdoors and set about overcoming those limitations through rigorous exercise (he managed to expand his chest to an almost comical level) and later went on to be a boxer and cowboy. A rising politician who, at forty, gave that up to fight in the Spanish-American War. An author, adventurer, and orator. A man who was once shot in the chest and went on to give his prepared 90-minute speech. And that is all without mentioning that he just so happened to be President of the United States at a time when that nation became a global power.

That sounds made up. It sounds like a boy dreaming of what a life could be. But it happened. And at the end of the day, if you are to only read about one president, you could do a lot worse than picking Teddy.

This is not to say he was a man without faults. After all, a faultless man would make for a dull biography. Teddy could be petty and argumentative. He was stubborn and often refused good advice. He was vain and egotistical and bordered on cruelty with his treatment of his former friend and later rival, Howard Taft.

But that is what makes him so fascinating. He is inspirational and infuriating. Brilliant and deranged. The famous line from Whitman’s Song of Myself might as well have been written about Teddy. “I am large, I contain multitudes.”

The historical reputation of Roosevelt is in the eye of the beholder. Conservatives can claim him for his often hawkish foreign policy. Liberals can claim him for his progressive economic beliefs and actions in trust-busting. He was at times a friend to business, at times a steadfast defender of workers. He was an ardent conservationist (the work he was proudest of) and an avid hunter.

Unfortunately, for this project, there’s not enough space to investigate the full breadth of a man like this. Morris wrote three excellent and exhaustive biographies on him, and I wanted more. There is no way for me to encompass even a modicum of Roosevelt’s life in the short space I have here (and even if I could, I wouldn’t dare, just read Morris’ books).

Instead, I will talk briefly about something I fixate on with Teddy—his perseverance and willingness to take risks.

It is not a coincidence that the man who, as a boy, physically overcame his ailments would go on to see life as a series of obstacles to overcome, but it makes his accomplishments no less impressive. He nearly gave up on public life when his first wife, Alice Hathaway Lee, died of kidney failure a mere eleven hours after his mother died. “The light has gone out of my life” was all he could write in his diary that day. For a time, he threw himself into his work as a New York State Assemblyman, but it didn’t take, and before long, he was in the Dakota Territory living the life of a rancher, having retired from politics.

Think of the different world we’d live in if he’d stayed there. He could’ve inspired some Larry McMurtry novels, a Yankee politician turned cowboy. It’s a movie I’d watch, but it is a far cry from the imprint on the nation and the world that Roosevelt would have (there is an excellent section of the first of these three books on him hunting down, arresting, and transporting a group of boat thieves.).

But the man who swore he’d never remarry or rejoin the political arena was back before long, newly married and running for Mayor of New York City. Part of this was down to his incessant need for movement. He was always a boy in many regards. It was as if he was making up for his boyhood years he lost to confinement. That energy wouldn’t allow him to settle into the life of a cattle rancher, but it’s important to note his perseverance here. It would become a defining trait of his life. He was not a man who was unfamiliar with setbacks, failures, and criticism. It is safe to say that without those things, he never would’ve been the man and the historical figure we know. After all, it is only a person who is willing to risk failure who can know great success.

I don’t mean to overstate the importance of some historical figure in my own life, but I will say that I often draw inspiration from Roosevelt. It’s not that I agree with all his politics (though I think most of his positions age quite well), but rather that I find the man inspiring. I have chosen a difficult field (writing) to find success in. The odds are long, and the likelihood of failure is high. Sometimes, I look in the mirror and wonder if it would be better to forge a safer path.

But then I think of Teddy, and I read his famous speech about the man in the arena, and I feel a chill run down my spine and know that I need to at least. I know that even failure is not truly failure because at least you tried. I’ll leave you with that speech and the sincere advice you read these books. They are enthralling and brilliant and have left an indelible mark on me.

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

Tell me that doesn’t give you chills.

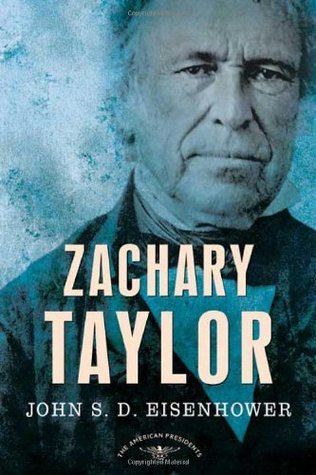

William McKinley

William McKinley was the president who straddled two centuries, established the United States on the Global stage, and was ultimately overshadowed by his successor.

The President and the Assassin: McKinley, Terror, and Empire at the Dawn of the American Century by Scott Miller

Tier 2

This book shares many similarities to Candice Millard’s book on James A. Garfield (Destiny of the Republic). Both discuss a president in sweeping but informative terms while also focusing on the events and characters that led to their respective assassinations. They are entertaining reads that describe a time and place in our nation’s history that seems to have been lost to time. I would highly recommend both and suggest reading them back-to-back if you wanted to bridge the gap between Ulysses S. Grant and McKinley’s successor, Theodore Roosevelt.

This book does not get a higher rating because it is not a comprehensive biography of McKinley, whom I found to be a fascinating and important president. That is not the fault of the book. Miller did not set out to write a detailed biography of McKinley, and he succeeded at writing the book he wanted, which deals extensively with Leon Czolgosz (his assassin) and the anarchist movement at large.

But this series of reviews is not about Czolgosz or Emma Goldman (the woman whom he pinned to impress by killing McKinley). It’s about presidents, and it's McKinley’s time in the spotlight.

William McKinley was the last president who served in the Civil War. This may seem like an inconsequential fact about the man, but I find it to be quite significant. The Civil War was (and still is) the defining moment in US history. The nation tore itself apart and nearly destroyed itself in the process. The events preceding and following that war are impossible to see except through its prism. It does not die with McKinley, but its influence and importance begin to fade once the White House is no longer occupied by a person who fought in that war.

We place an undo importance on the changing of a century (and round numbers in general). The world does not go through a greater change between 1899 and 1900 than between 1900 and 1901. But it feels different. It’s a moment to look to as the changing of the guard. And McKinley was an appropriate president to straddle those two centuries. He was a veteran of the Civil War and a man who, in some ways, was looking back. But he also saw the future that was coming for the nation and the world. In many ways, he inaugurated what one could argue has been the American Century for better and worse.

If you have read my previous posts, you already know a little bit about McKinley. He was the man who shepherded the McKinley Tariff Act of 1890. This Act raised tariffs on imported goods, which benefited American Manufacturers but drove up prices and upset the population overall. This is a common theme of McKinley’s economic strategy and beliefs. He prioritized American business, a philosophy known as protectionism.

As president, he is primarily known for his foreign policy. The United States was creeping toward becoming a global power since the Civil War. It was acquiring more land and massacring the American Indians who lived on that land while also building up its Navy and imposing its position on the global stage. McKinley solidified that position with Spanish American War and his broader foreign policy.

The Spanish-American war is complicated, and in many ways, it presages so much of the United States foreign policy in the years to come. Cuban rebels had fought for freedom from Spanish colonial rule for decades, only to be met with brutal reprisals. By McKinley’s presidency, the conflicts had broken into an outright war for independence. The American people supported the rebels, as did McKinley, but where the people seemed to favor military intervention on the side of the rebels, McKinley desired a peaceful resolution. Spain made it clear that it would not, under any circumstances, grant Cuba independence. Once riots broke out in Havana, McKinley agreed to send a battleship, the USS Maine, simply to be a presence in the area. Then it blew up.

Now I don’t have the time to get into all the various conspiracy theories surrounding the Maine and the subsequent yellow journalism that spurred the nation to war (Doris Kearns Goodwin’s masterful book The Bully Pulpit is a wonderful book that deals extensively with this time and these issues), needless to say, the United States Congress declared war on Spain.

One interesting point of note with this declaration of war was that it specified that the United States would not annex Cuba. The US was presented as a benevolent force attempting to assist freedom fighters in gaining their independence. This would be a strategy (genuine or otherwise) employed time and time again in American foreign policy.

The US Navy dominated their Spanish counterparts, and the distance from Cuba to Spain made resupply impossible, resulting in a swift American victory. This was a monumental moment in not only the US but world history. The plucky nation, which had only won its independence with the help of France, was now a power to be reckoned with. And the supremacy of the US Navy, at a time when Naval power was seen as the most important gauge of global power, was historic.

It is here that our story takes a rather unfortunate turn. No matter what you may think of the imperialistic ambitions of the United States, it would be hard to argue that helping Cuban rebels win their independence was a bad thing. But the peace treaty was not solely over Cuba, and the United States wound up taking over Puerto Rico and the Philippines, a group of islands halfway around the world that posed no immediate military threat to the United States. The subsequent pacification and treatment of the Philippines were horrific. It is a story that is not told nearly enough, and I won’t try to rush it through here as that would not do it justice. McKinley is not solely responsible for the atrocities committed in the Philippines, but he shares considerable blame.

In short, the Spanish-American War can be seen as a harbinger of things to come. You can choose to see it as a good thing, a moment when the United States helped the people overthrow their oppressive colonial rulers, or you can see it as an early example of American imperialism that led to horrific acts of violence against a native population. In truth, it is both. It represents the duality of the United States and the nation’s presence in the world. A beacon of hope or oppression, depending on whom you ask. The only thing that remains uncontested is that this was the moment the United States solidified itself on the global stage. The great powers of the world could no longer ignore it, and that is a primary legacy of William McKinley.

When assassinated, McKinley was seen as a near-pantheon-level president and a larger-than-life figure some suggested should run for a third term. It is one of the great ironies of history that he would be so overshadowed by his Vice President, a man primarily selected for the role because the Vice Presidency was seen as a place to ensure he had no real power, Theodore Roosevelt. But that’s next week.

Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison. He was president. Not a lot more to say, but I did my best.

Benjamin Harrison by Charles W. Calhoun

Tier 5

Benjamin Harrison was the great-grandson of William Henry Harrison, the ninth president who died after just thirty-one days in office. Unfortunately for Ben, that ignominious fact alone makes his great-grandfather a more well-known president than him.

If you’ve been reading my series on the presidents and their biographies, you will remember how often I have mentioned tariffs. This is because, aside from the Civil War and slavery, tariffs seem to have been the defining political issue of the nineteenth century. Nearly every biography discusses the president’s stance and legislation on tariffs.

In a way, this feels somewhat refreshing to me. Tariffs may be dull business, but at least they seemed to have a tangible effect on politics. I’m not sure I can say the same for today’s political arena.

Harrison’s tariff was known as the McKinley Tariff. It was named after William McKinley (more on him next week), and it raised the average duty on imports to almost fifty percent. This was meant to protect domestic industry and workers in the face of foreign competition. It is a prime example of protectionism, which was very much the Republican position at this time. The public did not like the McKinley Tariff as it caused an increase in the price of goods and led to inflation. As to whether or not it was one of the principal causes of the Panic of 1893, I cannot say. Economics is a complicated behemoth, and even in retrospect, the causes are heavily tainted by the politics of the historian.

There you go—some tariff talk. I’ve joked about tariffs quite a bit during this series, but I have to say some authors do manage to make it captivating. Tariffs have a tangible impact on the lives of citizens, and the long push and pull of protecting domestic industry and keeping costs low is interesting. I don’t know that I needed to spend as many hours as I did learning about them, but that is part of this project.

Calhoun doesn’t quite manage to make the tariffs all that interesting. Neither does he accomplish his apparent goal of reshaping Harrison’s legacy. He gives him substantial credit for his antitrust legislation, monetary policy, and tariffs. He also praises Harrison for his forward-thinking foreign policy—modernizing the navy, overseas expansion, and emphasis on the Monroe Doctrine.

It is no coincidence that these aspects of Harrison’s presidency are the ones Calhoun highlights. They are, of course, similar positions to those that Theodore Roosevelt held.

Teddy looms over all these post-Grant biographies, and I don’t blame the biographers for it. One may set out to write a biography on Benjamin Harrison, but in the back of your mind is always going to be the infinitely enthralling man to come. The swashbuckling cowboy who fought big business, built a canal, sailed down the Amazon… see, I’m doing it myself. Some giants loom over American history, and it is hard not to live in their shadows.

But let us give Harrison his due. The Sherman Antitrust Act was a monumental piece of legislation that remains in effect over 130 years after its signing. It was passed with bipartisan agreement and has been used countless times as a stalwart against monopolies and every growing stranglehold of big business. It does not guarantee a competitive arena or outlaw so-called “innocent monopolies.” Still, it does serve as a platform for the government to reign in monopolistic activities that abuse customers and artificially stifle competition. As with much legislation, some argue it went too far, others that it didn’t go far enough, but ultimately it was a step in the right direction.

Calhoun also points out Harrison’s work toward securing civil rights for blacks in the South. He endorsed the doomed Federal Elections Bill, proposed a constitutional amendment to overturn the Supreme Court ruling that gutted the Civil Rights Act of 1875, and tried to extend federal funding to all schools regardless of the race of their students. None of these attempts were successful, but Harrison never stopped pushing for Civil Rights.

Aside from that, I don’t have much to say about Harrison. He was known to be a man of integrity who was voted out of office because of his economic policies. He failed to win the popular vote in the election that put him in office, and while he laid some foundation upon which later presidents would stand, he is largely forgettable.

Calhoun sees him as a twentieth century president trapped in the nineteenth century. He thought his attempts at progressive legislation and imperialistic military expansion would’ve played well in the twentieth century. In this, he is correct. But, I believe he is retrofitting Harrison’s reputation around Roosevelt’s later success. It’s an admirable attempt, but it doesn’t work for me, and the book, in general, is a bit of a slog.

Groundskeeping

I recently finished an excellent novel by Lee Cole called Groundskeeping and was struck not only by the author’s voice but by the depiction of a time that I lived through and so viscerally experienced. The novel is about a young man, Owen, who takes a job as a groundskeeper at a small college to be able to take a course there for free. He wants to be a writer, is trying to right his life, and falls in love. In many ways, this is well-worn novelistic ground, but besides Cole’s excellent writing, what differentiates it is its setting—2016, a year seared into our national collective consciousness.

When I started this book, I had a hard time comprehending that 2016 was, in fact, seven years ago. It felt unfathomable that so much time had passed since that election and all that came with it. I suppose part of that disbelief exists because we still seem to live in that time. We’re gearing up for another election with many of the same characters. The same issues still blare through our headphones and televisions. Few people have changed their minds. Most have simply grown angrier.

I love history and novels (or films or television) that take place during a notable moment or era. Whether that be historical fiction or a film that was current when it came out but now serves as a monument to a time and place. I am particularly fond of the paranoid thrillers of the late sixties and early seventies. The post-Watergate mistrust of establishment mixed with some Vietnam-induced anxiety creates a potent cocktail. One of the things I love about those films is how they are both distinctly tied to a time and place and yet still feel current. They use the backdrop of their era to create a timeless narrative.

Those films, or the countless other times and places I’ve escaped to, happened before my time. They happened in a world that I could only ever read about. A world that history had judged and analyzed and (mostly) survived. Groundskeeping is one of the first novels I’ve read about a significant historical moment in which I was a witness.

Naturally, there have been many other pieces of fiction where I was alive during the events. I was alive during 9/11, for example, but I was a child. I lived it through the prism and safety of childhood. The 2016 election was not like that. I voted in it. I worried about it. I had interminable conversations about the participants and what was at stake. And I watched as the ground disappeared from under my feet.

Cole manages to depict the tension and anxiety surrounding that time brilliantly. Owen lives in the basement of his grandfather’s house as he tries to get his life back on track. His grandfather is a widower whose fifty-one-year-old son, Cort, lives with him. Cort is a Trump supporter. So is one of Owen’s coworkers. So are Owen’s mother and stepfather.

But his love interest, Alma, and another coworker and Owen himself are not Trump supporters. They detest him and all he stands for with a visceral hatred that bleeds through the page.

These people must coexist and, for the most part, often ignore their political differences. Every conversation Owen has with his two coworkers who stand firmly on opposite sides of the political fence does not revolve around politics. They don’t universally despise each other. And the reader is the same. You roll through sections of the novel, forgetting about various people’s political leanings. At least you do right up until the election.

This is what it was like. This was how it felt. It was an ever-present anxiety weighing on your every thought, but you still lived your life.

The novel does a beautiful job of depicting the social divide that exists in our nation. A campus was a logical place to set this conversation. There are the students, mostly liberal, and the workers, mostly conservative, and Owen straddles those two worlds. He eats reheated McDonald’s leftovers with his grandfather and uncle while they watch John Wayne films and avoid discussing politics, before he goes to a bar, where he basks in the irony and nostalgia of the left.

But the novel does not succeed solely because it accurately depicts these two worlds and that time and place. You need more to make a great novel. You need a soul. And Groundskeeping dug into me more because of the portrait of Owen than the politics of 2016.

Owen is in his late twenties after wasting years living a rudderless existence where he was a borderline addict. He’s not sober in the novel, but he is trying to exorcise his past and start fresh. Only he can’t. The person he was, left an indelible imprint on who he is, and the people in his life—Alma, his parents, his grandfather—cannot let that past go. It takes years to reshape who you are, but Owen longs to have it done in a swift stroke.

I’ve been there. I was there at almost the same time Owen was. It took me a few more years to turn things around. I was still drinking in 2016, still stuck spinning my wheels, still pretending that things weren’t as bad as they seemed (though I don’t think even I believe that lie anymore). But when I finally did begin to turn that corner, as Owen does in this novel, I was afraid that I could never undo what I’d done. Owen shares this fear.

I can’t tell you how often I read a passage and felt the author was writing about me. When Alma, his accomplished girlfriend, tells him that all his years spent working bad jobs and struggling were just research for his future as a writer, he responds, “I didn’t feel like an undercover writer… I felt like a failure.” Lines and sentiments like that separate this novel from similar ones I’ve read.

Cole rather brilliantly uses this character and this time to mirror one another. One of the primary issues that seems to dominate our current political discussion has to do with the past. It is about our national history and the way we tell our story. One side wishes that story to be one of triumph and unmitigated success. The other sees it as a horror story with closets full of skeletons we’d rather ignore. The truth is, both as individuals and as a nation, that we cannot escape our past. Just as Owen’s years spent living out of his car and struggling with addiction cannot be erased by getting a job and trying to become a writer. Our national scars cannot be erased with any one action. We cannot pretend they didn’t happen. I love how Cole folds those two narratives into one another and shines a light on our national conversation by using an individual.

It’s a lovely novel full of heart and humor and compassion. It’s political because to write about 2016 and avoid politics would be disingenuous, but it does not force politics into every conversation or onto every page. It’s an accurate representation both of that time and of what it’s like to try to fix your life in your late twenties. It’s a brave novel from an exciting voice reminiscent of Sally Rooney or Ben Lerner, and I can’t wait to see what he writes next.

Grover Cleveland

Only non-consecutive president, born up the street from me, really didn’t want anyone who wasn’t a white man to vote. Grover Cleveland this week!

An Honest President: The Life and Presidencies of Grover Cleveland by H. Paul Jeffers

Tier 3

A few interesting things about Grover Cleveland before we get started. He is the only president to have served two non-consecutive terms, which makes him both the 22nd and 24th president. He is the only president to have gotten married while in office. And, most importantly, he was born down the street from me (this is only interesting to me).

Now that we got those out of the way let’s get into Grover and Mr. Jeffers's biography of him. Cleveland is one of only two Democrats to become president in the period between the Civil War and World War II (the other being Woodrow Wilson). He rose through the ranks of New York state politics and was steadfastly known as an honest and straightforward politician. You may not have always agreed with Cleveland’s positions, but it was difficult to fault the man making them.

He was elected president in 1884 by winning four swing states (New York, New Jersey, Indiana, and Connecticut) by tight margins over his Republican opponent Blaine. Blaine had hoped to court some of the Irish Catholic vote, long a Democratic stronghold, due to his mother being Irish and his help to that nation during his stint as Secretary of State. This strategy seemed likely to work until a Republican gave a speech denouncing the Democratic party as the party of “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion.” The Irish Catholic voters did not care for this swipe and flocked back to Cleveland’s ticket.

There was additional tension regarding Cleveland’s campaign due to Tammany Hall, the Democratic machine that ran New York City. Cleveland didn’t like Tammany, and the feeling was mutual. Cleveland had spent much of his time as Governor of New York trying to root out political corruption, and Tammany was just a nest of corruption. Ultimately Tammany decided it would be better to have a Democrat who disliked them in the White House than a Republican.

Cleveland ran for re-election in 1888, winning the popular vote but failing to win the electoral college. The election again came down to those four swing states, and Cleveland could not carry his home state of New York and Indiana (Harrison, his opponent’s home state) and lost the election.

During Harrison’s presidency, Cleveland mostly worked and stayed out of politics until some of Harrison’s policies upset him to the point of speaking out. Cleveland opposed his financial plans (notably tariffs and a plan to tie the US currency to silver) and wrote an open letter about it. This thrusted him back into the spotlight and made him the front-runner for the 1892 Democratic nominee.

The 1892 election was one of the tamest in US history. Harrison’s wife was gravely ill with tuberculosis during the campaign, severely limiting his ability (or willingness) to campaign. She died two weeks before the election, and all the other candidates stopped campaigning. Harrison’s tariffs (seriously, it’s incredible how much these biographies talk about tariffs) had made imported goods more expensive, and voters flipped back to Cleveland.

Cleveland’s second term began with the Panic of 1893, which led to a depression. During this term, he campaigned against the Lodge Bill, which would have strengthened voting rights protections and, in particular, helped to ensure Blacks in the South could vote. They were, of course, constitutionally able to vote, but Southern Democrats had begun their process of finding ways to ensure they did not vote. Cleveland, as a Democrat, worked to kill the Lodge Bill.

Several labor disputes rose to national prominence during Cleveland’s second term, most notably the Pullman Strike. Cleveland sided against labor in this instance, claiming that the delivery of the mail, interrupted by this strike, allowed for a federal solution. He sent troops in to end the strike. The media and most of the political leaders of the day supported Cleveland’s actions. Still, in retrospect, it seems a harsh way to deal with workers who were appropriately striking for better wages and treatment. A significant point of contention in the strike was that Pullman’s company laid off workers, lowered wages, and refused to reduce the rents on the corporate housing (where workers were forced to live) or prices at company stores (which the workers were forced to shop at). Hard to look back on that one and side with Pullman.

After finishing his second term, Cleveland retired but kept a finger in politics. He occasionally was consulted by Theodore Roosevelt (the two had worked together during Cleveland’s time as Governor of New York when Teddy was in the Assembly there) and spoke out against woman’s suffrage claiming, “sensible and responsible women do not want to vote.”

Going through presidential biographies in a row is an interesting experience. You can’t help but look forward, and this period after Grant and before TR can best be described as “waiting for Teddy.” This book, in particular, dealt with that as Cleveland’s time as governor regularly references the man whose shadow looms so large in this era of American politics.

As for the book itself, it was a bit disappointing. Cleveland is an essential figure in American history who is largely lost to time. He was resolute in his opinions and, by all accounts, a principled man. Roosevelt looked up to him despite being from opposite parties. And yet, Cleveland’s legacy has aged poorly in many areas. This is a man worthy of an exciting and detailed biography, but this is not it. Perhaps there is one out there, and I picked the wrong one. I’ll let you know if I do.

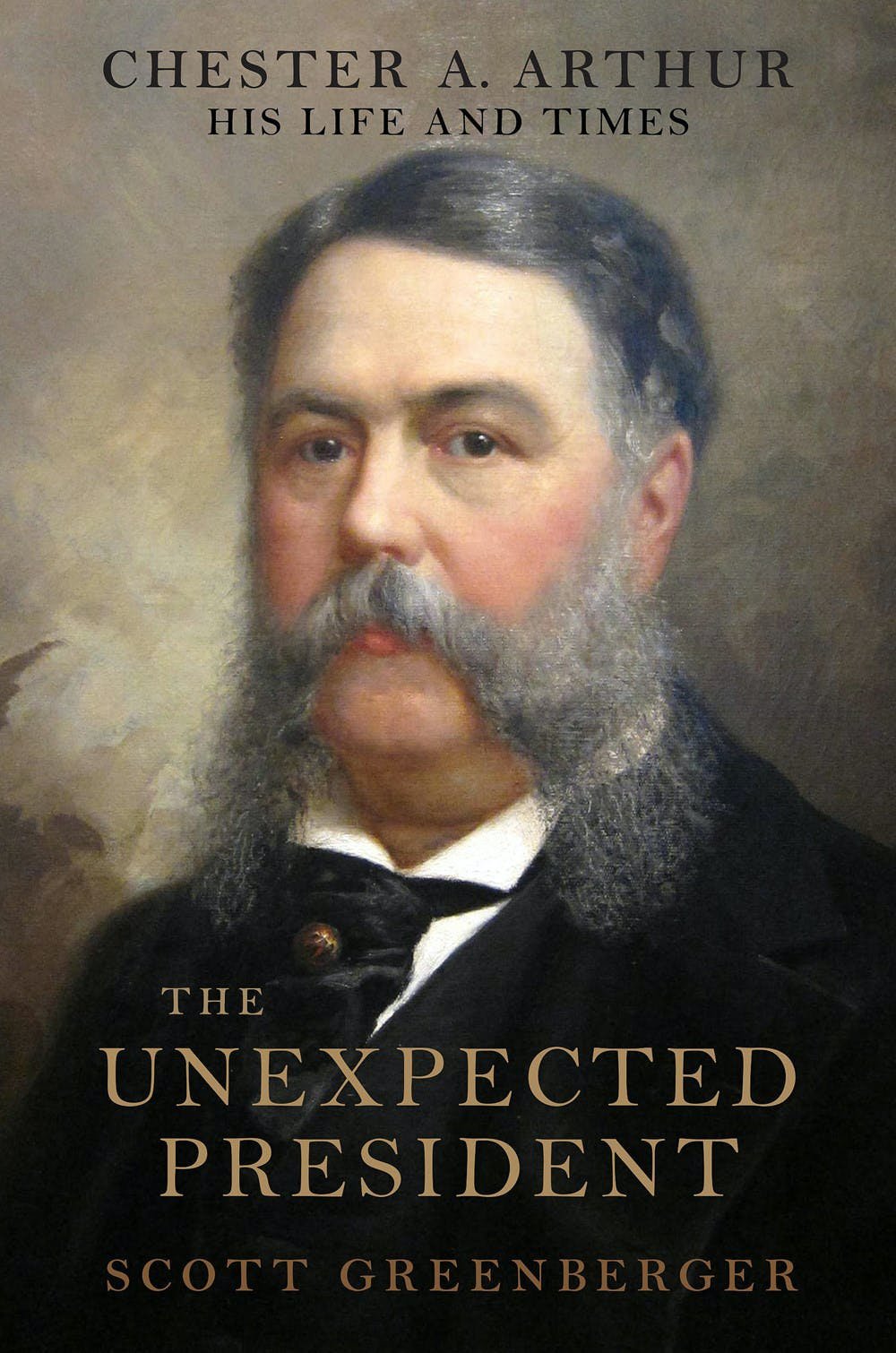

Chester A. Arthur

Chester A. Arthur. The Man. The Myth. The Mustache.

The Unexpected President: The Life and Times of Chester A. Arthur by Scott S. Greenberger

Tier 5

Say what you will about President Arthur, his facial hair was something else. Imagine waking up every morning and sticking with that look. That takes perseverance and dedication.

Jokes aside, Arthur is a nearly forgotten figure in American history. I mentioned in a previous post that the president does not define some eras of our nation’s history. We live in an age with a heavy spotlight on that position, but it wasn’t always like that. Sometimes, notably in the post-Jackson/pre-Lincoln years, the nation’s fortunes were governed by Congress and the larger-than-life figures who resided there. At other times, as in Arthur’s day, the country turns its eyes to industrialists and inventors. And this often leads to forgotten presidents. And Arthur would rank high on the list of forgotten presidents.

Arthur was born in Vermont. He was the son of a preacher and attended college in New York. He briefly worked as a schoolteacher before pursuing a legal career and eventually moving to New York City, where he became involved in Republican Party politics. He served as Quartermaster General for the New York Militia during the Civil War and saw no fighting. His real break in politics came during the Grant administration when he was named Collector of the Port of New York.

This was a great job. It was corrupt and sketchy and powerful and incredibly lucrative. As Collector of the Port of New York, you were in charge of bestowing thousands of jobs and made more than the President of the United States. Arthur received this position because he was a loyal servant of the Republican Party. He was not a man to make waves or discuss his personal convictions. He did what he was told, toed the party line, and kept the machine running. Did Arthur do questionable things while collector? Almost certainly, but that has a lot to do with what was deemed questionable. It was accepted at the time that you would use a position like that to reward loyal party members. And that’s precisely what he did.

Unfortunately for Arthur, the new president Rutherford B. Hayes had promised to reform the spoils system and made the New York Republican machine a particular point of contention. Arthur tried to make the cuts that Hayes wanted, but it wasn’t enough, and a committee appointed to review the Custom House was very critical of Arthur in their report. Arthur hung on for a while, but in 1878, Hayes fired him.

Arthur was a surprise addition to Garfield’s presidential ticket. Garfield, for that matter, was a surprise. Most people expected Grant to return and once again run for president with James G. Blaine, a senator from Maine who was more amenable to civil service reform than Grant, as the primary challenger. But things don’t always go according to plan, and Garfield secured the nomination.

Then, on the convention floor, Garfield’s men decided to offer someone from New York the Vice-Presidential nomination. They couldn’t go to Roscoe Conklin, the head of the Republican machine in New York, as it was too lowly of an office for him (I bet he regretted that when Arthur became president), and his eyes were fixed on the top job. So, they turned to a man named Levi P. Morton, who would later serve as Benjamin Harrison’s Vice President. Morton consulted with Conklin, who advised him against joining what he saw as a doomed ticket. Again, Conklin advised not to accept the nomination, but Arthur ignored the advice of his long-time mentor and patron and accepted.

The election was close with General Winfield Scott Hancock, a popular hero of two wars, running against them, but in the end, Garfield and Arthur prevailed.

It seems clear that Arthur saw the Vice Presidency as the height of his political career. There’s no reason to believe he pined for the top job, and when Garfield was killed, he seemed mildly horrified over the prospect of serving as president.

As president, Arthur passed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, which aimed to reduce political patronage and create a merit-based system for federal employment. This was quite a shock given that the spoils system had entirely formed Arthur’s career, but sometimes people surprise us.

There was a great deal in this book about Tariff Policy (the number of pages printed in presidential biographies about tariffs is staggering) and Naval expansion. Arthur suffered from health issues during his presidency, and despite considering a run for re-election, he understood it was not in the cards as essentially no Republican factions wanted him to run. After leaving office, he retired from public life.

So, what do we make of Chester A. Arthur? Fascinating and beguiling facial hair aside, he was forgettable. He was never elected president, and while the Pendleton Act was important, it’s hardly considered Arthur’s doing. He was a product of Conklin’s Republican machine, and it’s hard to see him as a more consequential figure than Conklin.

As for the biography, it isn’t memorable. Greenberger does his best, and you can see that he believes Arthur’s legacy should be more substantial than it is, but the argument is hardly convincing. Overall, I wouldn’t recommend it unless, like me, you’re a lunatic who intends to go through a biography of every president. Then have at it.

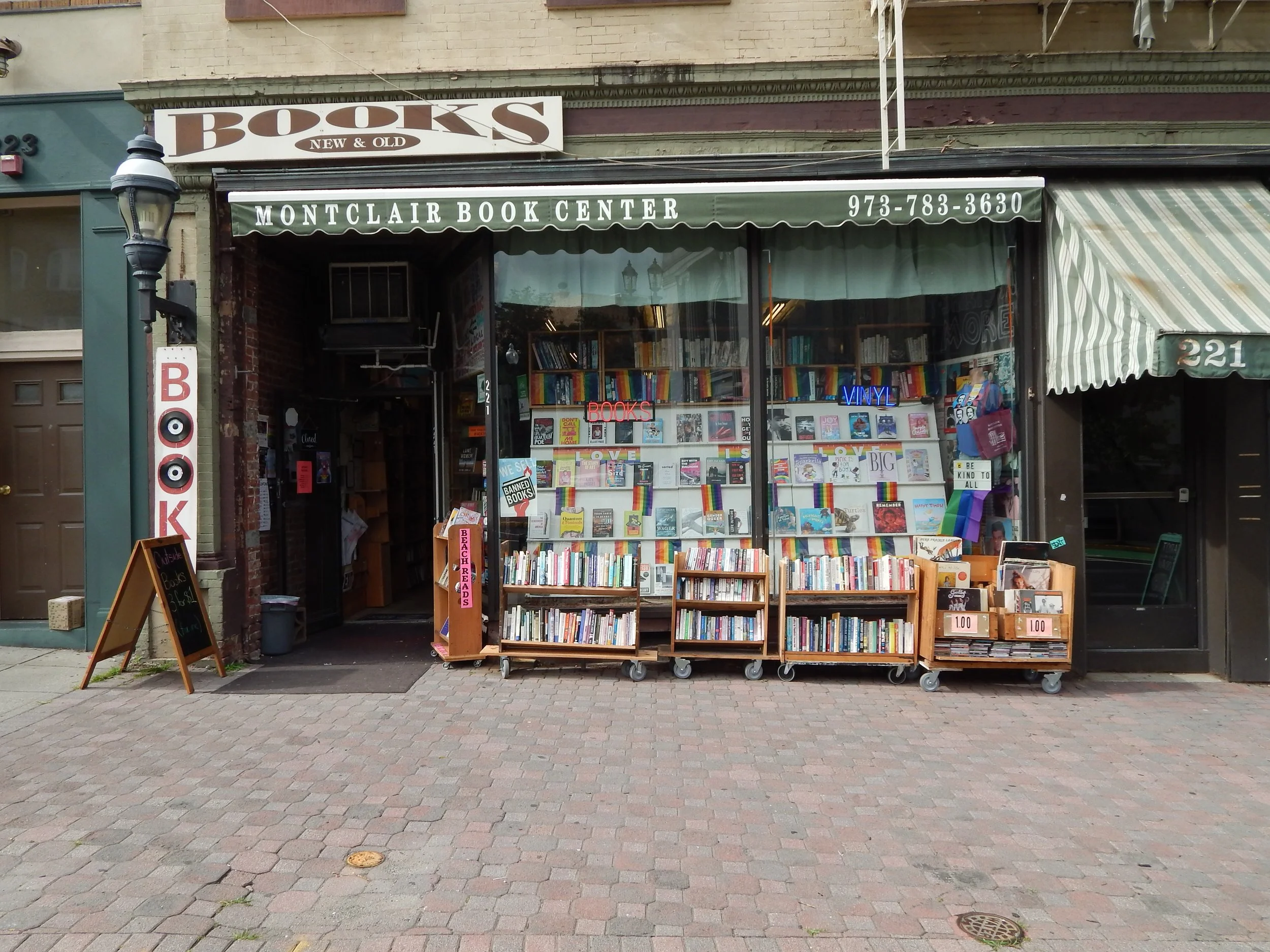

Montclair Book Center: Celebrating An Iconic Bookstore’s New Owners

Regal House Publishing originally posted this as part of their Book Bound Series. It’s a feature on the wonderful Montclair Book Center.

Regal House Publishing originally posted this as part of their Book Bound Series. It’s a feature on the wonderful Montclair Book Center. You can read it and their other additions to that series here.

When I close my eyes and picture a bookstore, the one that appears is Montclair Book Center. Rows upon rows overflowing with new and used books. Walls floor to ceiling with shelves of the same. A staircase that leads you upstairs from fiction to non-fiction. If you’d rather stay in fiction, you turn right at the stairs, and there’s another sea of books—children’s, sci-fi, fantasy. Deeper still, in the basement, are scores of records and an event space. They have rare books, first editions, comics, movies, anything your heart could desire lurks somewhere in this brilliant maze.

The store itself feels like a character from a novel. Like you wish you could get it to speak and tell you all its stories. It has a history to it. In the same way, a used book is special because you know someone else read and loved it, this store is special because of its past. You think of all the people who have walked in and gaped in awe at the shelves and the labyrinthine structure of the store. All the people who stopped by to kill a few minutes before dinner only to find, to their pleasant surprise, that they had missed their reservation. The moments when someone discovered a book or author they’d never heard of and suddenly fell in love. That’s the magic of Montclair Book Center.

It opened in 1984, but it feels older. It feels timeless like Montclair came to life around it, and if it weren’t there, the town would collapse.

I’m sure this is largely my own mythologizing. When I first started seeing my partner, we went to this bookstore. We had one of those days where you walk in expecting to spend fifteen minutes and emerge hours later with arms full of books and an inescapable joy coursing through your veins. It’s a fond memory we revisit every time we walk back inside and feel that excitement well up in us. I always feel like a kid inside those walls. I think of all the possibilities, the thousands of stories that live in that space. There’s a part of me that never wants to leave.

Chelsea Pullano and Ryan Whitaker bought the store a little over a year ago. They’d spent the last few years working for a start-up, knowing it wasn’t the right fit. They felt, as so many of us have over the past few years, that corporate life wasn’t for them. That years spent staring at a screen and working for somebody else wasn’t what they’d envisioned for themselves. So, they decided to make a change.

They didn’t set out with the intention of buying a bookstore. Instead, they had different visions, a café or a bar, some sort of place where people would gather. I can’t help but wonder if, after the terrifying isolation of Covid, this vision was born out of the need to connect with people and become part of a community, something larger than themselves.

Montclair Book Center happened on a whim. After a fruitless search for retail space, Chelsea decided to go rogue and see if any bookstores were for sale in the area. After all, if you’re looking for a place where people can go and get lost and connect, what’s better than a bookstore? And when she heard that her favorite bookstore, a place she’d spent hours wandering, was available, she was sold.

Chelsea had anticipated a hard sell with Ryan, a long process where she convinced him that this store in this town was the right choice. But in the end, all she needed to do was get him there.

“I took one walk through this place,” Ryan says, relaying the story. “And said, ‘This is the idea now.’”

Because that’s all it takes. You walk inside and feel both awed and comforted. You sense a familiarity as if every bookstore you’ve walked into before this one was preparing you to find Montclair Book Center. A common refrain you hear as you walk through the rows of books is, “This place is just so cool.”

As a longtime patron, I can say that Chelsea and Ryan are the exact people—so full of life and spirit—that you hope will take over your favorite bookstore. They aren’t some soulless corporation or, worse, a developer who plans to knock it down and build condos, but people who see the store's magic and want only to help it thrive for years to come.

They plan to utilize the store for more events—local authors are a particular area of emphasis. They stress the idea of it being a third space, somewhere that isn’t your home or work, where you can come to hang out and feel safe. In our increasingly difficult age, I can’t think of a place I’d rather spend my time than Montclair Book Center, run by Chelsea and Ryan.

“We’re all about community, sincerely, community and culture,” Ryan says. “We need to create spaces where people can come and learn and be seen and heard.”

There’s a crucial importance to a local, independent bookstore in the same way that a movie theater, restaurant, or school has value to a community. The new owners welcome this and are eagerly working to cement their status in Montclair. They’ve had young, aspiring filmmakers come in and shoot in their store, they’ve begun hosting events, promoting charity drives, and you can see this is only the beginning.

I asked them about books that inspired their love of literature, and Chelsea told me about discovering Wuthering Heights in high school and how it awakened something in her. Not only the novel but the way her teacher encouraged her to view and discuss it. You can see a glint in her eye as she envisions their store as a place where others can discover and discuss works that will awaken that same passion in them.

She also mentions being raised in a home with a “beautiful, leather-bound classics set,” which she devoured. I can’t help but wonder if having those at her fingertips influenced the person she’s become and maybe planted the seed to buy this store.

I wander the store for a bit and come across a delightful “banned books” display where they briefly explain why each was banned. It’s typical of the store, full of small corners where you can discover something new that stays with you. The display is also emblematic of the store's attitude and its new owners. There’s a defiance to them, a rebellious streak that drove them to make this leap. Leaving your corporate job to purchase an iconic bookstore takes courage, and I can see that Chelsea and Ryan are not lacking in that essential trait.

They have a wall downstairs in their newly renovated events space with a few polaroids hanging up of the authors who have held events. It’s a big wall, mostly empty right now, but I am confident they’ll fill it. I can already picture myself down there on a weeknight listening to some local author read from their new novel, and the vision fills me with hope. This is what a bookstore should be. A pillar of the community run by people full of hope and energy. I wish every community could have its version of Chelsea and Ryan running their independent bookstore.

My novel, A Campus on Fire, doesn’t come out until the Spring of 2025, but when it does, I can’t wait to have a reading at my favorite bookstore, Montclair Book Center.

I hope to see you there. It’s located in wonderful downtown Montclair at 221 Glenridge Ave. You can’t miss it, and I promise that once you’ve walked inside, you’ll never want to leave.

Visit their website, www.montclairbookcenter.com, to browse their excellent collection of new and used books. And to keep up to date on their events and other information about the store, follow them on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

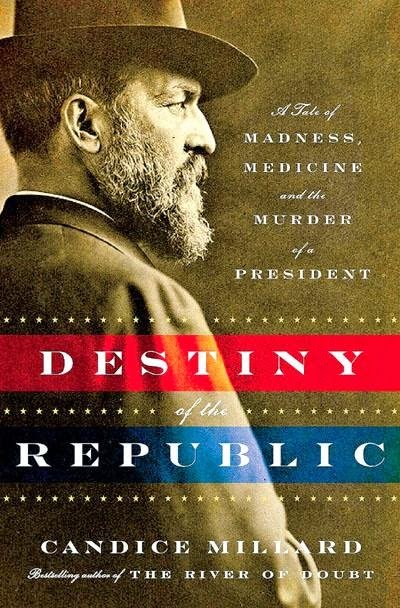

James A. Garfield

James A. Garfield (the president, not the cat). This is an excellent book that focuses on his assassination and the medical missteps that, if avoided, could’ve saved him.

Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President by Candice Millard

Tier 2

Over the course of thirty-six years, three presidents were assassinated. Of those three, Garfield was easily the least remembered. Lincoln is Lincoln. William McKinley (whom we’ll get to next month) was a well-regarded president in his own time, and his assassination led to the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, one of our most famous presidents. That leaves Garfield—the forgotten slain president in many regards.

He only served for a little more than six months, so it’s difficult to grade him out as a president. This can lead to historical revisionism, where historians judge him on his promises and do not ding him on his lack of execution. We get this same phenomenon with John F. Kennedy, consistently considered one of the better presidents in US history who accomplished very little.

Not that Garfield was a bad person or a bad president. He was simply an indifferent president in a string of largely forgettable presidents. There are stretches like this in the nation’s history where our nation’s idols came from places other than the presidency. (I think we are likely in or entering one of those stretches right now.) Robber barons and inventors, and the like outshined Garfield and his contemporaries.

Now, maybe, as some Garfield historians would claim, that would’ve been different if he lived. He was a rags-to-riches story (the last president born in a log cabin) who managed to form effective political coalitions and had considerable national charisma. Maybe he could’ve been a proto-Roosevelt or, at the least, a proto-McKinley. But we’ll never know, and ultimately his legacy has more to do with his death than his life.

So, let’s get to that death, as it is the primary subject of this book.

Garfield was killed by Charles Guiteau, a disturbed man who had convinced himself that he was in line for some sort of appointment due to his support of Garfield. This is, of course, strange, but politics did function largely on cronyism during that era.

After a series of attempted careers, Guiteau decided to gain federal office by supporting the Republican ticket. He even composed a speech in favor of Garfield printed by the Republican National Committee, but other than that had little impact on the election. Only, Guiteau didn’t see it that way. He seemed to believe he’d been instrumental in Garfield’s election and deserved a lofty posting. His preference was to be a consul in Paris.

Part of being president in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was listening to office seekers, and it seems that Garfield met with Guiteau at least once, but little came of these meetings. Guiteau then tried to discuss the position with other members of Garfield’s administration, focusing his efforts on James G. Blaine, Garfield’s Secretary of State, who strung Guiteau along for a bit before telling him he would not receive his desired posting.

Side note: I was amazed by the ease with which a person could contact high-ranking government officials at the time. When you compare that to today, it’s unimaginable that someone could manage meetings with the president and secretary of state with such flimsy credentials.

Long story short, Guiteau decides to kill Garfield and save politics in America. He shot him twice—once in the back, once in the arm—and was subsequently captured.

This is honestly where the book gets exciting. It’s less a biography than a story of these two men and medicine at the time of Garfield’s assassination. Millard argues that he would've lived if the doctors treating Garfield had simply listened to Dr. Joseph Lister, an early pioneer in antisepsis. There are some detailed descriptions of the unsanitary conditions upon which Garfield was operated that will make your stomach curl.

We are then introduced to Alexander Graham Bell, who tries to invent a machine that could locate the bullet still lodged in Garfield’s body, but the doctor in charge—Dr. Willard Bliss—limited its use.

In the end, Bliss is painted as a stubborn man who is unwilling to accept advancements that could’ve saved Garfield’s life.

Odd note: Robert Todd Lincoln, the eldest son of Abraham Lincoln, was present at Garfield’s assassination. He was Garfield’s Secretary of War and was, understandably, horrified by the events.

Millard does a beautiful job of illustrating this tragic moment in our nation’s history and how the intractable establishment often stymies progress. It’s an excellent read and is very well-paced.

The only reason this book did not receive a higher grade is that it’s not really a biography. It’s a book about Garfield that touches on his life before shifting to a story about Guiteau, medicine, and invention. Obviously, this is no fault of Millard, who doesn’t claim to have written a biography, and, honestly, I’d prefer to read this.

Rutherford B. Hayes

This week I wrote about Rutherford B. Hayes, primarily focusing on the Compromise of 1877 that ended Reconstruction, set African Americans in the South back to pre-Civil War conditions, and made Hayes president. It’s a sad, fascinating story and one everyone should know.

Rutherford B. Hayes by Hans Trefousse

Tier 3

When going through presidents, one can unfairly judge someone by comparing them to their predecessor. This is an unfair practice that has tainted many presidents. Is it Howard Taft’s fault that Teddy Roosevelt was president before him? No. Was it Lyndon Johnson’s fault that he followed a young, handsome, outwardly idealistic war hero John F. Kennedy? No. But they are always compared to those larger-than-life figures (we’ll get to each of them in their own time, and I assure you no one outstrips Johnson in terms of personality), justly or otherwise.

Hayes falls into that category for me. Not that he was some exceptional individual or president, but simply that he feels dull compared to Grant, one of my favorite figures in U.S. history.

Some basic facts—Hayes was born in Ohio, served in their House of Representatives, and eventually became Governor of that state; he fought for the good guys in the Civil War; and was elected president in possibly the most debilitating election in U.S. history. Ultimately that election is what he is known for.

Alternately known as the Compromise of 1877 and the Bargain of 1877, Hayes was elected under a cloud of controversy that resulted in the abandonment of both Lincoln and, later, Grant’s attempts at equitable Reconstruction in the South. As it is the primary thing Hayes is remembered for, let’s get into it.

In the 1876 presidential election, Hayes ran against Samuel J. Tilden, an anti-slavery Democrat formerly of the New York political machine. He ran on a similar platform to Hayes that dealt mainly with civil service reform which was all the rage in the late 19th and early 20th century. Despite Tilden’s support for the Union during the Civil War, southern Democrats (aka virulent racists) supported him hoping to be able to end Reconstruction in the South and return to the antebellum status quo. Would Tilden have gone along with this? We have no way of knowing.

Tilden won the popular vote by around 250,000 votes. He also won the electoral college 184 to 165. However, four states—Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina— returned disputed results. If any of these states went for Tilden, he would reach the necessary 185 votes to secure the presidency.

Three of the four disputed states—Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina—still had federal troops occupying them to maintain order post-Civil War. They ensured that African Americans could vote in elections and hold office. Each of these states had elected Republican governments and only loosely were able to maintain power under the constant threat of Democrat revolt.

Democrats controlled the House of Representatives, Republicans the Senate. There was a sitting Republican President—Grant—whose power was severely neutered following several scandals.

Ok, I think that brings us up to speed.

Congress passed an Electoral Commission Act to establish a fifteen-member body—eight Republicans, seven Democrats— to rule on the disputed states. This body rules along party lines in favor of Hayes, granting him all the disputed twenty electoral votes and, subsequently, the presidency. The only way for the commission’s findings to be overturned would be for both the Senate and House to reject them. The Republican-led Senate approved the results, and Hayes became president.

End of the story, right?

Wrong.

The nation was fragile, held together with tape and staples, if you will. The Democrats in the South, almost all of whom had fought for the Confederacy and longed for a return to the post-Civil War order, were fuming. They were on the precipice of revolt. And how would the nation handle a second Civil War so close after the bloody catastrophe of the first?

The Republicans were not inclined to find out and set about striking a deal with the Southern Democrats. There are other factors in the compromise—some money for the industrialization and recovery of the South and a railroad to pay off a businessman who helped negotiate it. Still, the crux was the removal of federal troops from Southern states and an end to Reconstruction. This amounted to the complete abandonment of African Americans in the South and a concession that racist Southern Democrats could resume their pre-Civil War practices. They couldn’t call it slavery, but they could do what they wished.

If you wish to know more about the horrors these Southern States inflicted upon their Black population, I highly recommend Douglas A. Blackmon’s seminal book, Slavery by Another Name. Suffice it to say, it’s awful. Blacks were disenfranchised, imprisoned on any and all pretenses, forced into labor that could only be called slavery, and often murdered on a whim. This continued until World War II, when they were again met with horrible treatment during and after that war.

Now, I won’t claim that if it weren’t for the Compromise of 1877, we’d be living in some racial utopia, but it’s hard not to pinpoint this moment as a turning point. It would always be a struggle to convince the white population of the South to reshape their society, but the nation should’ve tried. Ultimately, they did not because Republicans and Northern, anti-slavery Democrats cared more about their peace and financial prosperity than the lives and rights of Blacks in the South. This is a dark moment in our history, and its reverberations echo into the present day.

As for Hayes, this wasn’t his fault. He didn’t negotiate this compromise, but he went along with it. He removed the remaining federal troops from the South (Grant pulled them from Florida before leaving office) and didn’t fight to maintain the hard-fought rights won by blood for Blacks in the South.

Hayes attempted civil service reform, handled a railroad strike, and argued over currency during his term as President. Trefousse, the author of this biography, focuses more on these things than on the compromise that brought him to office, but it doesn’t take. When I think of Hayes, I think of 1877 and the abandonment of Reconstruction. I think of how those racist Confederates managed to shape the legacy of Reconstruction into one of carpet-bagging Northerners. I think of what it must’ve been like to have been a Black man in the South who watched the ravages of the Civil War and saw a brighter future snatched away from him in the blink of an eye. I think of the Black men elected to state governments who were summarily run out of office and tormented for having tried to rise above their perceived station.

This sad moment in our history is probably unfairly linked to Hayes. Historians are split on what Republicans should’ve done in this situation. Some say it was essential to avoid a second Civil War. Others say it was their responsibility to protect what the war had been fought over. I’m sure you can guess that I fall into the latter of these two camps.

Trefousse’s biography is not particularly memorable. I highly recommend Blackmon’s book. It is essential reading if you want to understand our nation’s history. It is not a biography of Hayes, but it is an important book and, quite frankly, better than this biography.

Ulysses S. Grant

This week I wrote about my favorite one-volume biography and one of my favorite Americans, Ulysses S. Grant. He was a man with flaws, a man who stumbled, a man who knew the taste of failure. But ultimately, he was one of the greatest individuals this nation has produced and an inspiration in so many ways.

Grant by Ron Chernow

Tier 1

One of the catalysts that led me to set out to read a biography of every president was reading this book.

My dad is the one who instilled a love of history in me. He’s a man with firm beliefs in who was right and who was wrong during a particular moment in history. I have countless memories of being a boy and listening to him explain a moment or figure in history with a passion and acumen that I will never forget and always admire. And likely, my dad’s favorite president and American is Ulysses S. Grant.

I purchased this book for him years ago as a gift and loved listening to him regale me with a story from it every time I saw him. Whether it was a recounting of Grant’s military genius at Vicksburg or his fight against the Klan as president, the story was always vivid and told with brimming excitement. Naturally, I had to read it myself.

After finishing the book, I found I couldn’t move on. I would read other things, but a part of me longed to return to the world of Grant. I had an itch that needed scratching, and the only thing for it was to read a biography of every U.S. President. So that’s what I did.

Unfortunately, few compared to this book. Chernow is one of the great American biographers, and this is his greatest book. He’s better known for his biographies of Hamilton (thanks in no small part to a little musical based on that book) and Washington, but this is the one. This is the book that all his other writing was leading to.

In the same way, Chernow set out to rehabilitate Hamilton’s reputation. He did the same for Grant here. No figure in American history was more unfairly and effectively maligned and besmirched than Grant. The cowards and traitors who lost the Civil War made quick work of creating a false narrative. The “Lost Cause,” as it’s become known, was, and still is, as pervasive as a weed. It’s why you still see fools flying Confederate Flags and claiming that the war was about States’ Rights. It’s a despicable narrative that should’ve died along with that racist failure that was the Confederacy.

And Grant was the primary victim of this reshaping of history. He was shown in comparison to the vaunted, heroic generals of the CSA, most notably Lee and Jackson. It was repeated, ad nauseam, that the Union only prospered because of brute force. That the talent and ingenuity, and bravery lay with the Confederacy. That the Union Generals were little more than butchers throwing men forth to their deaths. And Grant was the lead butcher.

But that wasn’t enough. They didn’t stop at simply belittling his military abilities. They went deeper. They painted him as a wild, out-of-control alcoholic who made countless follies during and after the war based on his alcoholism. They even went so far as to fabricate a story about him vomiting on his wife during intercourse to drive home the idea that he was some pathetic alcoholic.

Then they described his presidency as an abject, unmitigated string of failures. Everything he did was cast in the light of a corrupt, vindictive, incompetent man who never belonged in the White House.

Was any of this true? No. Not really. His presidency was not an unbroken string of successes, but it was far from the total failure these revisionist historians made it out to be. I would say, on balance, there was more good than bad in it. And as for the rest, it is a string of lies and exaggerations meant to disparage and destroy one of our greatest Americans.

Grant, in many ways, sufferers from living in the shadow of Lincoln. It was, of course, Lincoln who gave him the command of the entire Union Forces, a million-man army spanning the breadth of the nation. Lincoln, whose faith in him never wavered, saw in this man a kindred spirit. Ultimately, and not unfairly, the Union’s victory is seen as Lincoln’s. There’s nothing wrong with that. Lincoln stood steadfast in the face of constant setbacks and never hesitated from the path he was on. He deserves the credit, but so too does Grant.

I won’t spend much time discussing the various military points, strategies, or movements. I’m far from an expert on them, and if you’re interested in those kinds of things, read this book. I will say that the only military genius the Civil War produced was Grant. It was not Lee or Jackson. It was not Sherman or Sheridan. It was Grant. A man whose life had been shaped by defeat and knew that the only way to victory was moving forward. A man who commanded the entirety of the Union forces (Lee only ever had command over his Army of Virginia) and brilliantly deployed them to victory. And, if you need some specific tactical genius, just look up Vicksburg. Lee never could’ve pulled that off.

Grant is a figure of particular importance to me, given how his enemies dragged him for his alcoholism. It’s a despicable way to treat a man who, before there were any twelve-step programs or therapists, managed to mostly overcome his addiction and go on to succeed as he did. As someone who is quite a few years sober, I find this narrative appalling. We have a penchant in this nation, and as a species writ large, to focus on someone at their lowest. We seem to love to look down on someone and judge them forever by their failure. I choose to see Grant in the opposite vein. I do not, as Chernow does, try to dismiss his alcoholism. Instead, I see it as one of his crowning achievements. He was a man trapped in that familiar spiral and managed to pull himself out of it. That is not a story of shame. That is a story of victory.

There is fair and accurate criticism surrounding Grant’s presidency. He was embroiled in scandal, and it is appropriate to criticize him for that. Chernow works to excuse away many of those scandals, but I think it’s fair to hang them on Grant. If we are to believe he was as brilliant and sharp as Chernow makes him out to be, we can’t excuse the corruption by claiming he was simply too trusting a man (even if that is a contributing factor). Still, the scandals are all anyone seems to remember from his presidency, which is a shame. He fought for reconstruction and to ensure a more equitable South. He was a strident abolitionist and a champion of Black suffrage during his time as President. He fought and defeated the first iteration of the Ku Klux Klan, which at the time was a formidable domestic terrorist organization. And, if not for later concessions and failures, Grant would’ve been seen as the architect for a more equitable South. The fact that reality did not come to pass shouldn’t be placed on him.

I discussed last week how Lincoln’s depression and alleged failings were largely responsible for his success as president, and Grant is very much cut from the same cloth. After the Mexican American War, Grant was on the verge of poverty and drowning in alcoholism. He was a broken man. It is one of my favorite passages in Chernow’s book where Grant is at Galena, barely able to keep his head above water, as the Civil War hurdles toward him. If you had told someone who saw him then that he would go on to become the most acclaimed General in American history and the President of the United States, they’d have laughed in your face.

But that’s the thing. Life is long, and even when we sit in the depths of despair, there is a chance at a bright, glorious future. And it’s a man like that, who’s felt those failures, who’s known what it's like to taste defeat, who was needed to win the Civil War, the defining moment in American history.

There’s a story from Shiloh that’s one of my favorites. The Confederate army had surprised the Union forces and driven them back to the Tennessee River. It was raining, and Grant’s army was bruised and battered and all but defeated. Sherman had spent the day fighting in the middle of enemy fire. He’d seen the destruction the Confederate forces had wrought on the Union Army. He went out in that rain to find Grant and to discuss the best means for retreat. But when he finally found Grant standing under a tree, hat pulled down over his face, collar up, cigar chomped between his teeth, he reconsidered. Instead of mentioning retreat, he said, “Well, Grant, we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?”

And Grant responded, “Yes. Yes. Lick ‘em tomorrow, though.”

And, of course, that’s exactly what they did.

That is the story of a man shaped by failure and defeat. And that is a man who, perhaps, most exemplifies our nation at its best. Not a perfect man. Not a man who never stumbled. But a man who always got back up and pressed on. I cannot help but agree with my dad's unadulterated respect for Grant.

This is my single favorite one-volume biography. Not just presidential biography, mind you, but biography in general. Part of that is due to my love of discussing Grant with my dad, but most comes down to Chernow’s brilliant writing and Grant himself. A man we can all learn from both in failure and victory.

Andrew Johnson

This week I discuss David O. Stewart’s book about Andrew Johnson’s impeachment trial. It’s a good book about a terrible man.

Impeached: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy by David O. Stewart

Tier 3

We’ve spent a lot of time in recent weeks talking about the worst presidents. The Fillmore, Pierce, Buchanan run is a proverbial murderer’s row of bad presidents. They were, at times, actively harmful, but much of their well-earned dishonorable place in history stems from inaction. Andrew Johnson’s place in the pantheon of bad presidents was thoroughly earned through his actions.

Johnson was not Lincoln’s preferred running mate. It’s hard to envision two people sharing a ticket with such disparate views and temperaments. Lincoln chose him because he was a War Democrat (a southern Democrat who supported the war and had refused to secede) and wanted to demonstrate that he was committed to reconciliation. Remember, he made this choice while the Civil War was still raging, and he was already looking forward to the difficult work of restitching a severed nation together at the seams. Johnson seemed a logical choice.

And, of course, Lincoln didn’t anticipate getting assassinated. Presidents never do.

And when John Wilkes Booth fired that fateful shot and robbed us of our greatest president during a time that was, in many ways, just as perilous as the war he’d just led us through, we were left with Andrew Johnson. Arguably our worst president and likely the most despicable man to ever hold the office.

I don’t say this lightly. I understand all the horrible people who have held this office. And I believe Johnson to have been the worst, most despicable human being ever to call himself President of the United States.

Johnson started out well enough. He was actually quite vindictive toward the defeated Southern States in the early days of his presidency. But this was likely more out of petty spite than anything else, and his later actions would demonstrate where his heart truly lay.

He was an unapologetic and vocal white supremacist and a virulent racist. He wanted nothing more than to undo the gains won during the Civil War at the cost of hundreds of thousands of American lives. He felt that all Southern States needed to do to rejoin the Union was to accept the 13th Amendment (outlawing slavery). Many Northern politicians disagreed and felt that ensuring voting rights for Blacks was essential to Reconstruction. This would be a battle fought for a century wherein Blacks were disenfranchised, abused, murdered, demeaned, and, as Douglas A. Blackmon argues in his seminal work Slavery by Another Name, re-enslaved. This was what Johnson wanted. He wanted to undo everything Lincoln had fought for. He wanted to roll the nation back to its pre-Civil War status quo. For the most part, tragically, he succeeded.

This book is not so much about Johnson. We don’t learn about his childhood in Raleigh, North Carolina, or his time as Governor of Tennessee. We don’t read as he contemplates whether to go with the seceding Confederate States or stay with the Union. David O. Stewart instead focuses on his impeachment.

Johnson was impeached because he attempted to remove his Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, from office. Stanton believed a military occupation of the South was necessary to enforce Reconstruction. He had been very close with Lincoln and attempted to follow through on Lincoln’s plans for Reconstruction. Johnson, someone who had no interest in protecting the newly emancipated, disagreed with this policy. Congress, overwhelmingly Republican following the war and Lincoln’s assassination, saw where this was headed and passed the Tenure of Office Act. This act essentially denied the president the power to remove members of his Cabinet unless the Senate approved the removal and subsequent appointment.

Political history can be tricky. I hate Andrew Johnson. I hate everything he stood for and believed in. I hate the American South he represented and shaped. I hate the century of oppression and murder he helped to make possible. But I don’t think the Tenure of Office Act was appropriate. It violates the separation of powers that was laid out in The Constitution. No matter how abhorrent an individual he or she may be, the President of the United States should have the right, within reason, to pick their Cabinet.

As with every impeachment in this nation’s history, this wasn’t about violating the Tenure of Office Act. It was about Johnson. The Republican-led Congress despised him and what he stood for, and they hoped to remove him from office. They passed this act and then overrode Johnson’s veto with the express intent of him violating it and then impeaching him.

As I said, history is a tricky thing. If I’d been alive then, I’d have wanted nothing more than Johnson removed from office. The nation would be a far better place if Lincoln, or even Grant, had been president in the years following the Civil War. But I don’t know that they had a valid case for impeachment.

Technically though, that does not matter. You don’t need to have a strong case. You simply need the votes. And initially, it appeared the Republicans had them. Here the history is a little murky. Stewart is convinced that Johnson bought off key Republican Senators to win the vote. I will trust Stewart here as I have no reason to doubt it.

The book itself is quite readable. It’s exciting and well-paced, and recently, it found itself back on best-seller lists due to recent political turmoil. It’s worth noting that this book was not written in response to any subsequent impeachment. It was published in 2009 and avoided parallels to Nixon (notably not impeached) or Clinton.

I highly recommend the book. It’s very well written and researched. However, I did find it lacking as a political biography. It only covers the impeachment and does not take the reader through Johnson’s life or the other aspects of his presidency. Again, as in the past, this is my fault. I picked this book because it seemed interesting, and I wanted to know more about Johnson’s impeachment. Stewart does not claim it to be an exhaustive biography of Andrew Johnson. I will have to seek out another to learn more about this man I hate so much.

Abraham Lincoln

Finally, we emerge from the darkness and find Abraham Lincoln. Burlingame’s excellent two-part biography exhaustively details our greatest president and his complex, brilliant life.

Abraham Lincoln: A Life by Michael Burlingame

Tier: 1

Finally, we are through the wilderness. There will be other less-than-enthralling biographies and presidents to come, but that was the difficult bit. That stretch, from Jackson to Lincoln, is the part of this project where you question your sanity. But here we are. Safely through the darkness and into the light that is Abraham Lincoln. Our greatest President and the man who shepherded this nation through her darkest hour.

Unfortunately, it is impossible for me to adequately discuss Lincoln here. I don’t have the space to fully encompass the man’s life or Burlingame’s brilliant two-part biography on him. Do I talk about his early years in poverty on the Kentucky and Indiana frontier? How he taught himself and rose to first be a prominent attorney before turning to the Illinois state legislator and later a U.S. Congressman? Or do I talk about his debates with Stephen A. Douglas while they were both running for Senate in 1858 and how those debates served as a national discussion regarding slavery and the future of the nation? Perhaps I could delve into how those debates vaulted Lincoln to national prominence while also serving as a harbinger for the future of American electoral politics. Or maybe it’s best to discuss the Civil War, the defining moment in American history, which he led us through. I could discuss the perils and failures that he faced during that war. The cowardly generals and the resilience to keep going. Or would it be best to discuss his famous cabinet of rivals or even his tragic assassination? Or, given the closeness to Juneteenth and the ongoing fight for racial justice in this nation, should I discuss Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and his legacy in that area?

It’s too much for one post. Even Burlingame couldn’t fit it into one book, and let me assure you, they are not short books. So, as I have done in the past and will have to do in the future, I will instead focus on one or two specific aspects to focus on.

Abraham Lincoln, our greatest president and perhaps the greatest American, struggled throughout his life with depression. He had a litany of causes for his often-debilitating depression. He lost an infant brother and his mother when he was just a boy. He watched the latter die in a small, one-room cabin. A pain and trauma that I think most of us cannot even comprehend. He had one remaining sister, Sarah, with whom he grew very close after she took the mantle of running the Lincoln home. Then, ten years after his mother died, Sarah died during childbirth.

What a childhood to have to endure. The idea that he rose from those early years, moved on his own to Illinois without a penny to his name, and went on to achieve anything is remarkable. The fact that he reached the heights he did is simply staggering.

But even at those heights, the depression lived in him. It lingered and reared its head from time to time. When he would have failures, say a bill not passing or a military defeat, he would sink into the lonely quicksand that is depression. He would see the world as hopeless and wish to withdraw. He frequently contemplated suicide and once wrote, “I am now the most miserable man living. If what I feel were equally distributed to the whole human family, there would not be one happy face upon the earth.” Friends even went so far as to remove razors from his rooms and keep an eye on him in case the worst was to come. This was in his thirties, twenty years before he became president and led the nation through its darkest days.

I think it’s hard to view his life and its trajectory and not feel these bouts of depression influenced his leadership style. Was he able to handle more failure than your average man because of his experience with the depths of depression? Had he, in his difficult years, learned coping mechanisms that would later serve him well? Or was it merely that a man accustomed to depression was the right man to shepherd us through a national depression?

There is a different, perhaps related, aspect of Lincoln’s personality that I was struck by when reading Burlingame’s excellent biography, his shameless love of learning. Burlingame tells a story of Lincoln, as president, asking a fellow guest what a word meant and how to spell it. Lincoln, one of the greatest minds our nation has ever produced, a man who rose from nothing and could easily have been guarded or embarrassed by his lack of formal education, was so desperate and shameless in his quest for learning that he opened himself up for ridicule.

It's funny when you’re reading one of these massive, multi-volume biographies, it’s often the little things that stick with you. And I could just picture Lincoln, tall, lanky, beaten down by the pressure of the Civil War and his lifelong battle with depression, leaning over the table to ask someone to tell him what a word means and how to spell it. I could see the light in his eyes that never went out. The one that was there to learn new things, to embrace the wonders of an often-crushing world. It’s a wonderful image I always think of when contemplating Lincoln.