James A. Garfield

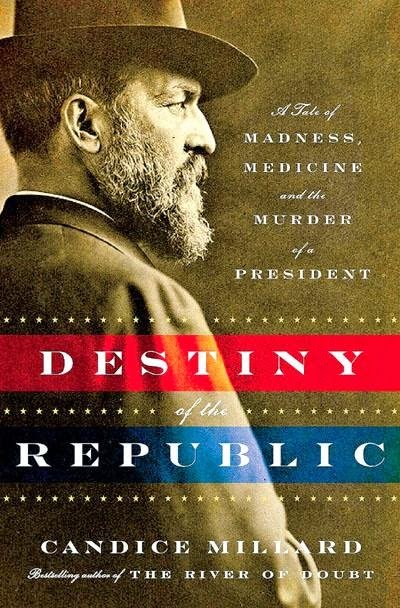

Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President by Candice Millard

Tier 2

Over the course of thirty-six years, three presidents were assassinated. Of those three, Garfield was easily the least remembered. Lincoln is Lincoln. William McKinley (whom we’ll get to next month) was a well-regarded president in his own time, and his assassination led to the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, one of our most famous presidents. That leaves Garfield—the forgotten slain president in many regards.

He only served for a little more than six months, so it’s difficult to grade him out as a president. This can lead to historical revisionism, where historians judge him on his promises and do not ding him on his lack of execution. We get this same phenomenon with John F. Kennedy, consistently considered one of the better presidents in US history who accomplished very little.

Not that Garfield was a bad person or a bad president. He was simply an indifferent president in a string of largely forgettable presidents. There are stretches like this in the nation’s history where our nation’s idols came from places other than the presidency. (I think we are likely in or entering one of those stretches right now.) Robber barons and inventors, and the like outshined Garfield and his contemporaries.

Now, maybe, as some Garfield historians would claim, that would’ve been different if he lived. He was a rags-to-riches story (the last president born in a log cabin) who managed to form effective political coalitions and had considerable national charisma. Maybe he could’ve been a proto-Roosevelt or, at the least, a proto-McKinley. But we’ll never know, and ultimately his legacy has more to do with his death than his life.

So, let’s get to that death, as it is the primary subject of this book.

Garfield was killed by Charles Guiteau, a disturbed man who had convinced himself that he was in line for some sort of appointment due to his support of Garfield. This is, of course, strange, but politics did function largely on cronyism during that era.

After a series of attempted careers, Guiteau decided to gain federal office by supporting the Republican ticket. He even composed a speech in favor of Garfield printed by the Republican National Committee, but other than that had little impact on the election. Only, Guiteau didn’t see it that way. He seemed to believe he’d been instrumental in Garfield’s election and deserved a lofty posting. His preference was to be a consul in Paris.

Part of being president in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was listening to office seekers, and it seems that Garfield met with Guiteau at least once, but little came of these meetings. Guiteau then tried to discuss the position with other members of Garfield’s administration, focusing his efforts on James G. Blaine, Garfield’s Secretary of State, who strung Guiteau along for a bit before telling him he would not receive his desired posting.

Side note: I was amazed by the ease with which a person could contact high-ranking government officials at the time. When you compare that to today, it’s unimaginable that someone could manage meetings with the president and secretary of state with such flimsy credentials.

Long story short, Guiteau decides to kill Garfield and save politics in America. He shot him twice—once in the back, once in the arm—and was subsequently captured.

This is honestly where the book gets exciting. It’s less a biography than a story of these two men and medicine at the time of Garfield’s assassination. Millard argues that he would've lived if the doctors treating Garfield had simply listened to Dr. Joseph Lister, an early pioneer in antisepsis. There are some detailed descriptions of the unsanitary conditions upon which Garfield was operated that will make your stomach curl.

We are then introduced to Alexander Graham Bell, who tries to invent a machine that could locate the bullet still lodged in Garfield’s body, but the doctor in charge—Dr. Willard Bliss—limited its use.

In the end, Bliss is painted as a stubborn man who is unwilling to accept advancements that could’ve saved Garfield’s life.

Odd note: Robert Todd Lincoln, the eldest son of Abraham Lincoln, was present at Garfield’s assassination. He was Garfield’s Secretary of War and was, understandably, horrified by the events.

Millard does a beautiful job of illustrating this tragic moment in our nation’s history and how the intractable establishment often stymies progress. It’s an excellent read and is very well-paced.

The only reason this book did not receive a higher grade is that it’s not really a biography. It’s a book about Garfield that touches on his life before shifting to a story about Guiteau, medicine, and invention. Obviously, this is no fault of Millard, who doesn’t claim to have written a biography, and, honestly, I’d prefer to read this.