Woodrow Wilson

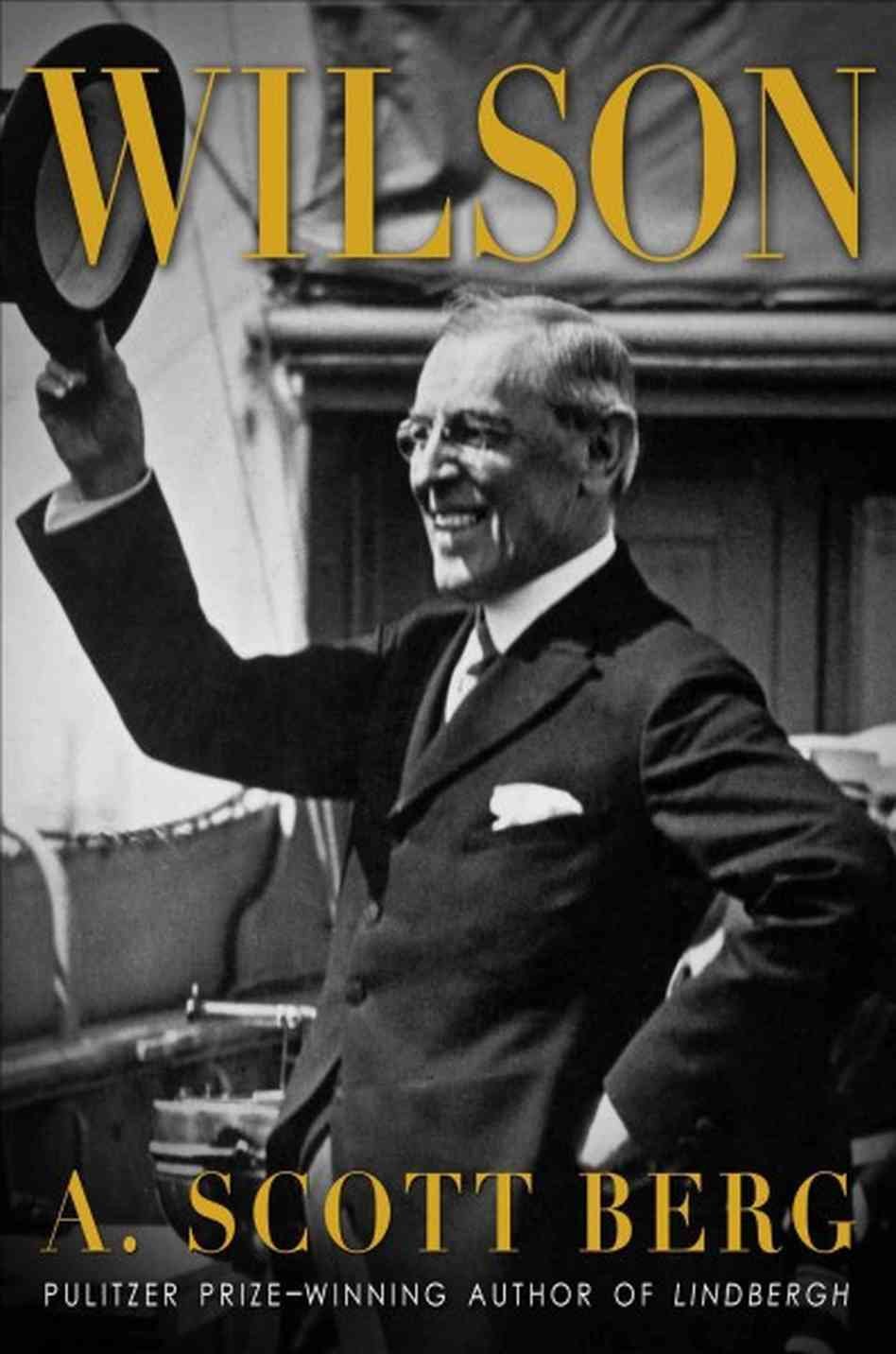

Wilson by A. Scott Berg

Tier 2

Woodrow Wilson was an unlikely president. He was an academic, former president of Princeton University, and a relatively unremarkable governor of New Jersey when he ran for president. He was not a man known to possess excessive charm. He did not have some great moment to lean back on. And yet, he became one of the more influential presidents of the early twentieth century. Over a hundred years later, his foreign policy and progressive ideals still exist in our national discourse.

But he is also a prime example of how politics can shift, and one's historical reputation changes along with it. For a long time, Wilson was seen as an exemplary liberal. One who pushed for a global order and a peaceful resolution of conflict. One who fought for progressive policies in education and workers' rights. And yet, he was a virulent racist and fought against women’s suffrage. What do we make of these kinds of presidents?

He was not a bad governor, but he felt he was unlikely to win re-election. He had spared with his party machine and pushed forth a progressive agenda as governor, but these acts didn’t make him many friends in New Jersey politics. But he carried the state even though the Republican Taft won it in the 1908 election. From that win, not his later governance of New Jersey, he was tapped for a run for president.

As I mentioned in my post on Taft, there is great debate surrounding Wilson’s presidential victory in 1912. Some scholars would contest that Wilson never would’ve stood a chance against either Taft or Roosevelt had they run on their own. I am more skeptical of this idea. Roosevelt and Wilson ran on a similar platform of progressivism and the intervention of the federal government to correct income inequality and destroy corporate trusts. They likely cannibalized each other’s voters as much as Roosevelt and Taft.

The key to Wilson’s victory was that voters saw what they wanted in him. He courted three-time Democratic nominee and populist icon William Jennings Bryant’s support, securing Democratic progressives to his cause. But he also was a Southerner, raised in the Reconstruction South. The Southern Democrats saw him as a man who would fight against racial equality and women’s suffrage. This two-pronged approach was well-executed and won Wilson the election.

It is also worth noting that Roosevelt lacked the support of one of the two major parties. He got about as close as you can get in our modern two-party state to making it fight without one of those parties' support, but in the end, even Teddy couldn’t get that one over the line.

Wilson’s presidency began with a focus on domestic politics. Ironically, a man remembered for his foreign policy seemed to have no interest or expertise in that arena upon his election. Instead, he was more interested in natural resources, banking reform, antitrust legislation, helping farmers (a pet project of Bryant for years), and that old standard, tariff reduction.

History is a fickle master, and we do not get to decide who will be in charge in significant moments of strife and opportunity. As a nation, the United States was fortunate to have Lincoln in office at the onset of the Civil War. They were unfortunate at other times. The people history remembers tend to be those in charge during these historic moments, for better and worse. Neville Chamberlain was considered an average (or above average) Prime Minister before Munich. Even at the time, Munich was seen as a success, and his handling of the situation was overwhelmingly positive in England.

On the other hand, Churchill was a bit of a joke at the time of Munich. He was seen as a war monger and a failure—a colorful figure who shouldn’t be anywhere near the top job. And now look at them. Churchill is one of the great figures of the twentieth century. Chamberlain is a punchline.

Wilson would likely have been a forgotten president had it not been for The Great War. And even then, he worked to keep the United States out of that war. He campaigned on his success in keeping the nation neutral in the face of global catastrophe. He assured the nation that he would keep Americans off the battlefields of Europe.

That election was decided more on domestic issues, and Wilson won re-election. Not long after that, Germany began a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. They felt that, regardless of what Wilson claimed, the United States' efforts to supply the Allies with war provisions was a declaration of intent. Wilson could claim neutrality all he wanted, but his actions were seen as anything but neutral. When the Lusitania was sunk, Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war, and the rest was history.

The Allies would’ve won the war regardless of US intervention, but the introduction of such a large and prosperous nation on the side of the Allies certainly sped up the conclusion. The United States entered the war at an ideal time. They could claim to have brought about peace and assured their position in the post-war discussions. Other nations would argue that the sacrifice of the United States did not compare to that of long-term combatants, but Wilson’s position was established, and he could push for his post-war order.

There is a wonderful book called Paris, 1919 by Margaret MacMillan, which I would highly recommend if you are interested in the conclusion of World War I. It was one of the first history books I devoured and holds a special place in my heart. MacMillan is a fantastic writer, and that peace conference is well worth an entire book.

I do not have the time or space to dissect the Paris Peace Conference, the Treaty of Versailles, or Wilson’s Fourteen Points. I can say that no one gets everything they want, and the path to ruin is paved with good intentions. The Treaty of Versailles is perhaps most famous for setting in motion events that would lead to the most horrific war our planet has known. I firmly believe that we shouldn’t separate the two world wars but instead see them as one long conflict with a two-decade freeze.

Wilson wanted to fight for self-determination and a non-punitive settlement that could set Europe aright. He wanted people to be able to decide how they were governed and for nations to learn to settle their agreements in an international League of Nations. These are lovely ideas. They are liberal and progressive, and it would have been great if they had worked.

Part of the failure falls on Wilson. He was not a good enough politician to sell these ideas to his colleagues in Paris or at home. He failed to bring any Republicans with him to the peace conference, a horrendous political blunder and did not focus nearly enough on selling it to the people. In the end, he compromised on most of his fourteen points. Notably, he allowed France to enact the exact punitive vengeance on Germany that he swore to prevent and gave up on self-determination whenever it was politically expedient (mainly concerning the vast imperialist holdings of the Allies, a defining issue of the war). And he failed to get even his own nation to ratify the peace treaty or join the League of Nations. At one point, there was a potential compromise, but Wilson rejected it and ended any discussion of the United States ratifying the treaty he had worked so hard to finalize.

What do we make of this failure? It was on him. He was not the politician he needed to be to form a new world order. It would’ve been interesting to see someone with Roosevelt’s handle on the bully pulpit try to get it over the line. The United States was isolationist at the time. They would still hold that position at the outbreak of the Second World War. It was a challenging issue to change their minds on, but Wilson did himself no favors.

And his compromises in Paris are difficult to swallow. It is one thing to have lofty ideals and quite another to stick to them. MacMillan's book does an excellent job showing how intractable the other parties were. The war had been long and bloody, and France, in particular, wanted their pound of flesh. But I do not believe we can praise Wilson’s ideals without condemning his failure to see them through.

And that is Wilson in a nutshell. He is a great theoretical president but not a great actual one. He was a man who spoke of a beautiful world but did not work to create that world. It is difficult for us to reconcile these types of men. We want people like Wilson to reflect our views. We want heroes we can hold up and venerate. But it doesn’t work like that. He was a racist. He initially opposed women’s suffrage and seemed to change his mind when he realized they would vote for his party. Unfortunately, he failed to enact his grand visions, and his legacy is that failure. Paris in 1919 set the table for Munich in 1938, and Wilson deserves much of the blame for the failures in Paris.

This does not mean we have to ignore the ideas. It does not mean there are no great lessons to be learned from his rhetoric. But we need to take the whole, not just the parts we like from history.

Berg’s book is very good. It is comprehensive and engaging, but I feel it over-glorifies Wilson. I believe Berg is too quick to forgive his failings and cast blame on others. This is a common failure of biographies. The writer sometimes falls in love with their subject and can adorn rose-colored glasses when discussing difficult moments. It does not mean that you shouldn’t read this book, but only that you should view it with that in mind.