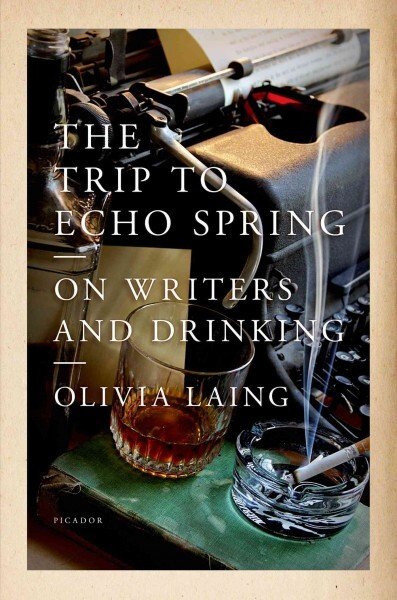

The Trip to Echo Spring - On Writers and Drinking Spring by Olivia Laing

This week I listened to one of my favorite books. It’s called The Trip to Echo Spring: On Writers and Drinking by Olivia Laing. As you could likely guess, it's a book about writers and alcoholism. She details the lives of six American authors – F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, John Cheever, John Berryman, and Raymond Carver. Each of them an alcoholic. Each an iconic writer.

I want to preface this post by saying I will not come close to accomplishing what she did in this book. It’s a flawless text. She writes non-fiction like Joan Didion, a novelistic approach to fact. Her language is beautiful, and the book flows like one of the great works by the authors she’s discussing. I won’t manage to do here what she does in her book, but I can talk a little about what it means to me.

Some of you likely already know that I’ve struggled with addiction. I’m happy to say those struggles are long behind me, but a book like this speaks to something in me as a writer who spent too many years drinking.

If I’m being honest, I think part of the romanticization of alcohol for me – which was essential in my drinking – came from stories about the authors Laing details in this book. I had a vague notion that I wanted to be a writer and saw alcohol as an essential part of that. After all, what makes one an author more than drinking?

Well, writing, obviously, but I wasn’t about to do that. To write would be to try. It would be to take a risk, to put myself out there, to show the courage of my conviction. If I picked up the proverbial pen and began to write, I might fail. I might discover it wasn’t in me, and then… what then?

So, instead, I drank. If I couldn’t write like Hemingway, I could at least drink like him. And I told myself that, like these icons of American letters, I was troubled. Deep, ponderous questions lived in me and could only be exercised by writing or drinking.

It’s incredible how ridiculous the mind of an addict is. The way we rationalize. The way we excuse our horrible behavior and continue to destroy ourselves.

Now, I never wrote anything when I drank. I told people I wrote. That wasn’t hard because I, like all alcoholics, was a liar. It’s an unavoidable hazard of the occupation. Sometimes I’d take a notebook on a family vacation, sit at a table, drink coffee, and pretend. I liked that. Pretending. I wanted to imagine I was something else, someone else, something other than an embarrassment.

It wasn’t until I got sober that I began to write.

And therein lies the paradox. Because I’d come to believe that a writer needs to drink and that the two occupations are inextricably linked. But I found it to be the opposite.

Had I been lied to? Had I concocted a false narrative?

Yes, obviously. It’s a narrative that stretches far beyond writing. There are countless other fictions about successful people and their connection to addiction (alcohol and otherwise). We’ve been taught, for some reason, that drinking is what one does. That a successful person is entitled to sit down at the end of a hard day and drink. This is what a man does. This is what’s expected.

If you ever needed to be disabused of this fiction, read Laing’s book. Yes, these authors managed some writing while they drank. Some of Carver’s early stories are quite good and were written before he got sober. Cheever was drinking as he wrote some of his iconic work, including perhaps the most remarkable of all stories on alcoholism – The Swimmer. But it wasn’t because of booze that they wrote. It wasn’t the thing that made them good. It didn’t help. And in the end, it destroyed them.

Hemingway’s most significant periods of writing always seem to coincide with stretches when his drinking tailed off. And it's no coincidence that Fitzgerald and Williams ended their careers having gone years without producing anything of substance. They’d succumbed to the bottle and, in doing so, had lost their spark.

Laing’s book is part biography, part memoir, and all genius. She paints vivid depictions of these men, highlighting similarities and touching on broad-scale thoughts about alcoholism. Sometimes our characters spend time together, and we see how alcoholics interact and deflect. She shows they’re all similar, but no two are identical. I think that’s always important to realize. We may all share a trait, but that doesn’t mean we’re the same people.

She discusses her connection to alcoholism and why she used only men in this work. She mentions the litany of other alcoholic authors she could’ve picked and leaves you, after a book so full of futility in the face of alcohol, with hope.

Carver, the last author she details, stayed sober. He resurrected his life from the depths of despair. He got to the other side. He made it.

I don’t know what will come of my career as a writer. It’s only beginning, and while I am excited by the potential, I understand it’s a hard road and the odds are against me. But I know that my life is better sober. I’ve experienced the pain, and the destruction alcohol can leave in its wake. I felt these stories that Laing details. I saw myself in those men, not in their highs, but in their lows. The waking up full of horror and uncertainty over what you’ve done, knowing you need to quit but being unable to take that step.

Laing finishes the book by referencing one of Raymond Carver's short stories, Nobody Said Anything. It’s about a boy who pretends to be sick to skip school, goes fishing, and brings home a fish. He’s proud of this fish and shows it to his parents, longing for their approval, only for it to be met with disgust. She writes about this story and alcoholism:

“We’re all of us like that boy sometimes. I mean we all carry something inside us that can be rejected; that can look silver in the light. You can deny it, or try and throw it in the garbage, by all means. You can despise it so much you drink yourself halfway to death. At the end of the day, though, the only thing to do is to take a hold of yourself, to gather up the broken parts. That’s when recovery begins. That’s when the second life – the good one – starts.”

It's such a hopeful way to end this book. It is, in my experience, true. I know many of you don’t struggle with addiction, so I appreciate you putting up with me. But if anyone is reading this and wondering if they might have a problem, please know it does get better. There’s another life, and I can’t tell you how wonderful it can be.

If you’re a person like that, please don’t hesitate to contact me. You can contact me through my website, patrickrodowd.com. Alternatively, there are countless resources online or in person, and, of course, you can read Laing’s brilliant book. I came to it post-sobriety, but I’m sure it could help you see the light.

As always, if you know someone who might like this, please tell them about my substack, website, or both. It would be a great help to me. Thanks for reading!