Andrew Jackson

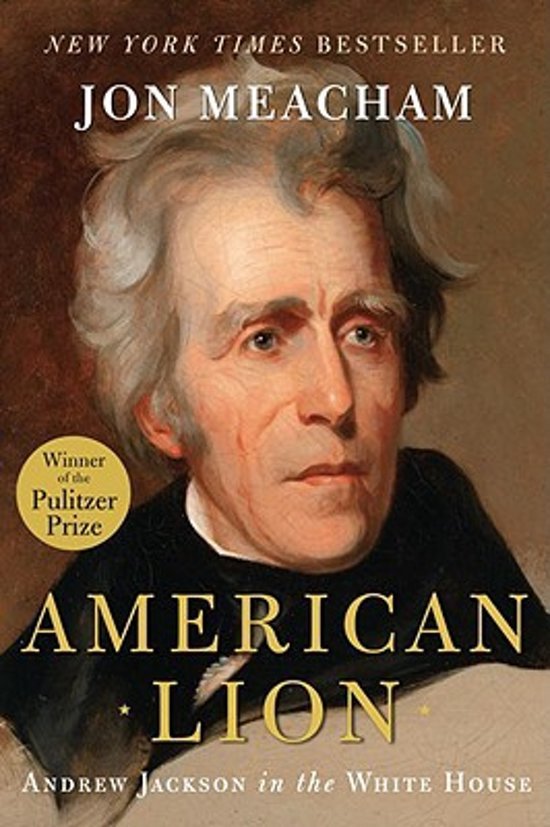

American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House by Jon Meacham

Tier 2

Two posts in one day?!?! Sorry about that, but I was on vacation last week and decided to post them both this week.

Fortunately, the two presidents I will post about today fit well together. Andrew Jackson nearly won the 1824 presidential election that put John Quincy Adams in office. I discuss this in my previous post, but I’ll mention some of the basics for posterity. Jackson won the popular vote and the electoral college but failed to win a majority of the latter. As such, the election was sent to the House of Representatives, where John Quincy Adams was elected. Let this be a small lesson for everyone who clamors for a third party in this country. I’m not saying I disagree with it, but other rules would have to be adjusted to avoid the House deciding every presential election.

Jackson would comfortably win the 1828 election when it was a race between himself and the incumbent Adams. The two men could not be more opposite. Adams was as blue-blooded as they come – the son of a founding father and the second president, an ambassador to European nations, educated at the finest schools. He was also opinionated and ornery, instilling little love or devotion from even his most loyal supporters. On the other hand, Jackson was born to Scotch-Irish immigrants in the Carolinas. He rose to become first a frontier lawyer and later a Tennessee Supreme Court Justice before turning his sights to the military. He led soldiers in Creek War and later in the First Seminole War. He was a fierce advocate of democracy (at least his specific vision of it) and engendered a godlike following. The two figures could not be more dissimilar.

Due to this stark parallel and their indelible link in history, Jackson’s presidency is seen as a clear line of demarcation. He took aspects of Jefferson’s populism but pushed it much further than his predecessor could’ve imagined. Jefferson, for all his lofty ideas of democracy, was an aristocrat. Jackson was not.

Meacham’s biography of Jackson is, in many ways, masterful. Again, there is a later one of his on this list that I prefer, but I think this is his defining work. Much like his biography of Jefferson, it is a bit short for my taste, but this isn’t on Meacham. He makes it clear in the title that this is a book about Jackson’s time in the White House and not an exhaustive biography of the man. As such, Meacham doesn’t waste too much time on Jackson’s early or later years. We don’t receive a detailed discussion of his military accomplishments (wildly inflated by Jackson himself). What we do get is a beautiful tapestry of the American political scene during his presidency and a detailed portrait of the complicated man, Andrew Jackson.

I should mention that going into this book, I did not like Jackson. I still don’t. I find it impossible to look past his horrific racial stances and the genocide he codified into law with the Indian Removal Act. I also find his particular brand of populism to be dangerous and troubling. We have seen his like many times since, and it is always a problem.

That being said, I truly enjoyed this biography. Meacham doesn’t claim his subject to be an angel. He doesn’t excuse his treatment of Native Americans or blacks. I’m not even sure that Meacham likes Jackson (not that this should matter in a biography). But it would be impossible to tell the story of the United States without talking extensively about Jackson and his presidency.

Jackson is a figure that divides opinion as much as any US President. You will see people defending him as a champion of democracy and a fiscal conservative who was intent on restoring the nation to its people. You will see others who decry him as a racist and an egomaniac bent on seizing as much power as possible. (It’s incredible how often history repeats itself, isn’t it?)

A wonderful section of this book discusses the period during his presidency when a civil war nearly broke out. This was known as the nullification crisis and centered on a controversial tariff (you have no idea how much of these early biographies were about tariffs and banks). I won’t get into the weeds here but suffice it to say the nation teetered on the brink of a Civil War. Things got so contentious that Jackson’s Vice President, the despicable John C. Calhoun (there’s a fantastic biography of him I’ve listened to and might write about after we get through the presidents), resigned and ran for Senate to better argue for nullification.

How did Jackson handle the situation? With strength. He told South Carolina that they would be met with fire and brimstone if they continued down that path. In the end, South Carolina acquiesced to a compromised Tariff, and both sides claimed victory while kicking the can down the road.

This is emblematic of much of the pre-Civil War period in the United States. The issues that would eventually lead to war constantly showed themselves, only to be temporarily resolved. A fracture was clearly coming, and these political battles were like tremors preceding an earthquake.

Did Jackson do well to avert a Civil War? Did he instead teach a generation of Southerners that war was coming and that they would do well to prepare for it? Would the abolitionist Adams have incited a war? Would we, as a nation, have been better off getting this inevitable war out of the way before military power advanced to the level it did in the 1860s?

These are questions largely without answers. It is my opinion that war was always coming. Jackson forestalled it, and a different president, one without the military background and reputation for reactionary violence, may not have been able to do that. I don’t think you can blame him for avoiding war. Still, he wasn’t interested in tackling the systemic issues (notably slavery, which lurked in the shadows of all pre-civil war discussions) that were endemic in the nation.

His reputation has, appropriately, waned in the past decades, but if you were to discuss the most consequential US Presidents, he would have to be in that conversation. As such, this biography is essential to someone interested in learning more about US history. It shows you Jackson and brilliantly portrays his presidency. It’s not as exhaustive as some other biographies, but it’s magnificent at handling the subject matter it chooses to discuss. Sometimes that’s better. Meacham focuses on a specific period of Jackson’s life and uses that era to illuminate the individual and his time.

(I still don’t like him.)